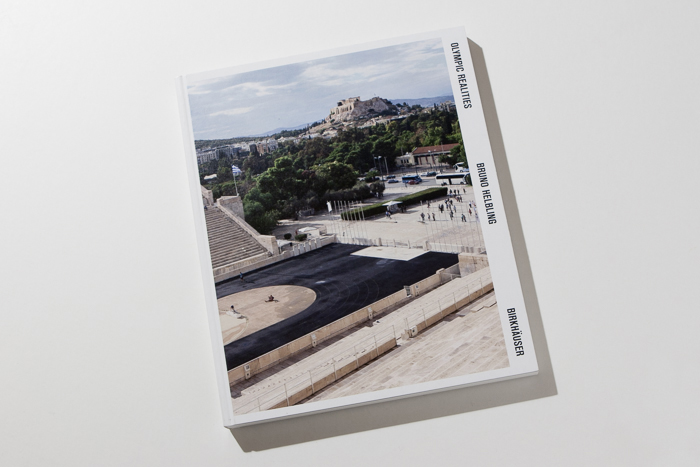

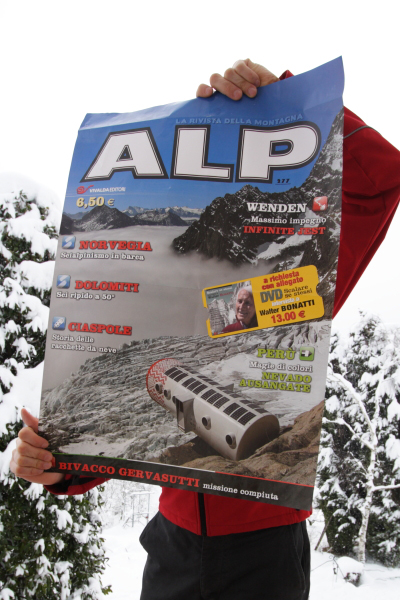

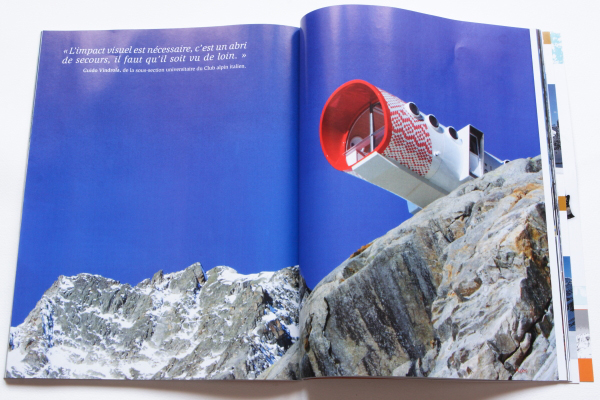

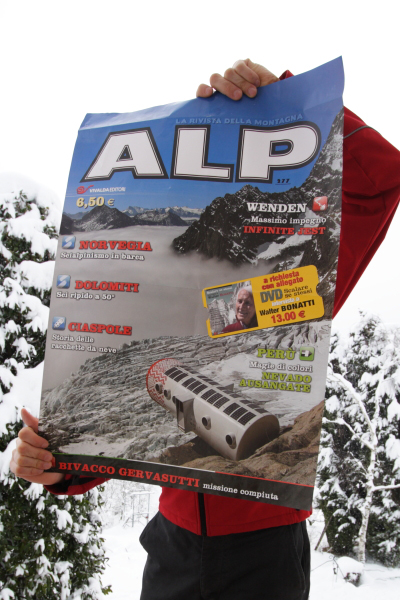

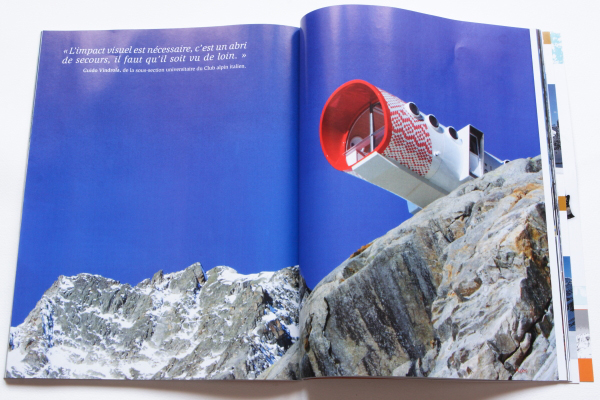

Mentre forse trovate ancora in edicola (se non lo trovate più lo potete sempre scaricare qui) il numero 277 di Alp con il mio servizio sul Bivacco Gervasutti che si è guadagnato la copertina del giornale, proprio in questi giorni la rivista francese Alpes (numero 133) ha pubblicato un articolo illustrato dalle mie foto. Mi rendo conto dell’ironia di pubblicare foto relative ad un medesimo argomento su due riviste di montagna dal titolo omofono (ma non omografo) però giuro che sono pubblicazioni indipendenti l’una dall’altra!

Dopo il primo resoconto, mi ero ripromesso di scrivere qualcosa a proposito della realizzazione di un servizio così complicato. Ci provo adesso.

Partiamo col dire che il progetto architettonico e costruttivo era di per sé complesso. Era il primo edificio del genere mai assemblato, mai portato in quota e mai montato e c’erano dunque da risolvere numerose difficoltà tecniche da parte sostanzialmente di tre categorie: architetti/costruttori, elicotteristi e montatori specializzati che avrebbero lavorato in quota. Ora è chiaro che chi va lì per fare le foto mette le proprie esigenze in coda a quelle di tutti gli altri cercando poi al momento giusto di far valere quelle due o tre richieste che fanno la differenza fra il fare o non fare una foto, fra il farla da schifo o portare a casa una buona immagine. Si aggiunga a questo che c’erano sul posto altri operatori foto-video più o meno embedded, più o meno importanti (vuoi non dare una priorità al cameraman RAI? eh, no, capisco e mi adeguo). Quindi dopo aver fatto le prime foto del montaggio a Courmayeur al momento di organizzare lo shooting in quota iniziano a porsi i primi problemi. Per chi non lo sapesse, il rifugio è infilato in una valle laterale della Val Ferret a qualcosa come 3-4 ore di cammino su terreno difficile e con passaggi di roccia. Si valutano quindi le seguenti possibilità: salire a piedi un giorno in cui il rifugio è finito e fare le foto. Salire a piedi il giorno stesso del montaggio e fare le foto. Salire a piedi il giorno prima del montaggio, bivaccare (in modo da essere sicuri di esserci al momento giusto), e fare le foto il giorno dopo. Ottenere un passaggio in elicottero. Pagare/Farsi pagare un passaggio in elicottero.

E’ evidente che salire insieme alla squadra di operai sarebbe la soluzione migliore, tuttavia è anche la cosa più difficile da ottenere vista anche la presenza di altri colleghi. Nelle settimane che precedono i lavori, mentre altri risolvono i problemi relativi al montaggio e si aspettano le condizioni meteo favorevoli io contatto a ripetizione: gli architetti, l’ufficio stampa CAI, il comune di Courmayeur, gli elicotteristi, l’impresa di costruzioni, la redazione di Alp (per cui sto preparando il pezzo). Dopo innumerevoli “forse” arriva finalmente un “forse sì” e arriva anche una data: giovedì. Bene, anzi no. Mercoledì pomeriggio ricevo una telefonata da una delle poche persone con cui non ho parlato fino a quel momento, è già in macchina e sta salendo in Valle con un altro fotografo perché entro sera vogliono provare a portare su almeno la base. Cavoli! Non riesco ad essere su in tempo, chiedo conferma che i lavori continueranno il giorno dopo. Quando ci risentiamo a sera scopro che in poche ore hanno già montato 3 moduli su 4 più la base, resta da montare l’ultimo pezzo ma non è detto che ci sia posto per me sull’elicottero. Va beh, decido di andare su la sera stessa per capire cosa si riesce a fotografare. Arrivo in macchina sul posto, tiro fuori il sacco a pelo e dormo lì. Prima dell’alba cominciano ad arrivare le altre macchine. Ci si conta, ci si presenta, ci si prepara, ma di certezze sul mio lavoro ce ne sono ancora poche. Prima del sole arriva anche l’elicottero, il suono si sente da lontano prima che la sua ombra nera si stagli contro la sagoma dell’Aiguille Noire (vedi foto).

Poi in un attimo qualcuno chiede “quante persone ci sono da portare su?”, vengo incluso nel conteggio, è fatta.

Pochi minuti dopo arrivo sul ghiacciaio solo per vedere l’elicottero che sale, passa e scende riportando a valle l’ultimo modulo perché è troppo pesante. Il resto della giornata trascorre sulla cengia fotografando i lavori di sistemazione e aspettando un nuovo tentativo di trasporto che non ci sarà.

A sera si scende e si fa il punto della situazione: forse domani. Con una faccia tosta senza limiti trovo qualcuno che mi ospiti la notte ad Aosta (risparmiare un po’ di chilometri, tempo e sonno non è una cattiva idea) e il mattino dopo sono di nuovo in Val Ferret. Non succede molto fino a dopo pranzo, poi nel pomeriggio finalmente arriva l’elicottero e nel giro di pochi minuti si monta il tutto. Abbracci, sorrisi. A sera invece di scendere decido di restare a passare la prima notte nel rifugio. Siamo in due, abbiamo da mangiare anche se io sono senza sacco a pelo. Ma il freddo e la notte insonne valgono la possibilità, grazie anche alla luna piena, di fare delle splendide foto dal tramonto all’alba della struttura finalmente finita e senza persone attorno. La mattina dopo, stanco dalle notti in bianco, con uno zaino di 13 chili pieno zeppo di attrezzatura fotografica scendo la pietraia (grazie, riscaldamento globale! Una volta era tutta neve) che sembra non finire mai.

Ecco come le foto del montaggio dell’ultimo modulo che dovevano durare poche ore si sono trasformate in una trasferta imprevista di tre giorni. Casa, doccia e via a scaricare le immagini. Ne è valsa la pena, no?

Una galleria di immagini è adesso anche sul mio sito.

————————————

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

(Kindly provided by Ricarda)

You might still find number 277 of Alp containing my reportage about the refuge Gervasutti at the kiosk (if not just download it here), where my photo made it to the cover. However, now the French magazine Alpes (number 133) published an article showing my photos. It is quite ironic that I have pictures about the same topic published in two mountain magazines with almost the same name, but believe me, they are absolutely independent from one another!

After a first summary I was determined to write about the difficulties of such a photographic service. I will give it a try now.

Let me say that the architectural and construction project was already very complex by itself. We are talking about the first assembled building of its kind, as it has never been done in high altitude and never been assembled before. Therefore there had been quite a number of technical problems concerning mainly three topics: architects and construction workers, helicopter pilots and fitters who needed to work in high altitude. It goes unsaid that if you want to go and take your pictures your needs obviously come last. Your job is to try to get the best out of a couple of questions that make the difference between taking or not taking a picture, getting a good shot or not getting anything decent. Furthermore there were other photographers and video services of major and minor importance (The cameraman from RAI does come first. I understand that and I try to adapt.) After taking a couple of first shots of the assembly at Courmayeur I needed to organize the shooting in altitude and problems started to arise. In case you did not know the refuge can be found in a small valley next to Val Ferret. It takes about 3-4 hours of hiking on difficult ground, some of that even on rock. There are 5 possibilities as to how to get the shooting done: Hike up on foot one day after the refuge is completed and take pictures. Hike up the same day of the assembly and take pictures. Hike up one day before assembly, sleep there (just to be sure you will be there at the right time) and take pictures. Get a lift in the helicopter. Pay or have someone pay for a lift in the helicopter.

It is quite obvious that getting up there with the fitters would have been the best solution, alas it was also the most difficult thing to implement since I was surrounded by fellow photographers. During the weeks before the works, while others solved problems regarding assembly and organisation and everyone is waiting for the right meteorological conditions, I am repeatedly calling: the architects, the CAI’s press office, the municipal administration of Courmayeur, the helicopter pilots, the construction firm, the editorial staff of Alp (I am writing the article for them). After countless “maybe” finally I get a “maybe yes” and a date: Thursday. Perfect. No, wait. Wednesday afternoon I get a call from one of the few people I had in fact not talked to yet. He was already driving up the valley with another photographer since they decided to bring up at least the base until evening. Oh crap! I will not make it in time, so I ask if the works will continue the next day. Next time we speak I find out that in a couple of hours they managed to assemble 3 modules out of 4. The last piece will be moved the next day, but a doubt remains on whether there will be a place for me on the helicopter. Oh well, I decide to drive up that very same evening to try and find out what I will be able to shoot. Once I arrive I spend the night in my sleeping bag in the car. Before sunrise more cars arrive. A quick count, some presentations, more preparations. Only I have no certainties about my work. Even the helicopter arrives before the sun. I could hear the sound way before his black silhouette could be seen against the outline of the Aiguille Noire (see picture).

And somehow suddenly someone asks: “How many are there to take up?”, I am included in the count, it is done.

I arrive on the glacier only a couple of minutes later and have to watch the helicopter moving up the last piece, passing by and moving back down the valley with the last module. It was too heavy. I spend the day on that little ledge shooting the works, waiting for a second attempt to bring up the piece that will never come.

Getting back to Courmayeur in the evening the decision is: maybe tomorrow. With a certain impudence I actually find someone who can host me for one night in Aosta (saving a couple of km, time and sleep is not a bad idea) and the next morning I am back again in Val Ferret. Not much happens until after lunch. Then in the afternoon the helicopter arrives and within a couple of minutes everything is set and done. Hugs, smiles. In the evening I decide to stay and spend this very first night in the refuge. Actually there is two of us, we have something to eat, but I did not bring my sleeping bag. But who cares about the cold and night when you have the possibility to take some amazing pictures with the full moon out of the whole structure, from sunset to sunrise, without anyone around. The next morning I am knackered from a night without sleep. With more than 13 kg of photographic equipment in my backpack I start hiking down the debris (Thank you so much global warming! All this used to be snow.) that somehow seems to have no end.

And that’s how the pictures of the last module and it’s assembly which were supposed to take up a couple of hours ended up as a mission of three days. Home, a nice shower and downloading the pictures. It was worthwhile though, wasn’t it?

You can find an image gallery on my site as well.